FAST FACTS

• The Casino’s artificial ice surface was the the first known in North America.

• The Casino was the first place in Pittsburgh where organized ice hockey was played.

• The building had the most modern indoor lighting:

– 1,500 incandescent lamps

– 11 arc lights

– 4 white calcium lights

• The Casino lasted less than two years before being destroyed by fire.

The following are excerpts related to the first hockey exhibition in Pittsburgh on December 30, 1895:

“The local men put up a pretty good game, but they are as a lot of boys with shinny sticks as compared to the past masters of the art form from across the border.” 6-0 score in polo. Visitors won “without half exerting themselves. The ball went sailing from one to the other in a manner so mystifying that the local team scarcely knew where it was most of the time. The Canadiens used the regular hockey sticks, which are longer and broader at the end than the small polo sticks used by the home team.”

… “demonstrated the superiority of that game over the one played here. The flat puck that is used slips around on the ice much more smoothly than does the polo ball, and the rules of the game allow much more scope for team work. The local team are talking strongly of giving up polo and adopting the Canadian game.” – Pittsburgh Press, December 31, 1895

The body of ice has remarkable smoothness and the excellence of its surroundings is unsurpassed anywhere on the globe.

PITTSBURGH PRESS, May 1885 newspaper article describing the Casino’s indoor frozen surface

Pittsburgh’s First Indoor Ice Skating Rink

Pittsburgh’s first multi-purpose arena was ahead of its time – by more than 100 years.

The Casino, operated by the Schenley Park Amusement Company in Oakland, was the envy of the sports and entertainment world. It was considered to be one of the “handsomest amusement buildings in the United States,” according to an Atlantic Architecture report. Luxury boxes, a grand theater, a capacity of 12,000, and an indoor ice skating surface made it an unrivaled complex in North America. The Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette called the Casino “the magnificent palace of pleasure.”

But as much as it was ahead of its time, it also had a short lifespan. The place burned to the ground just 19 months after opening.

In that time, however, the Casino left an impression on modern hockey. It was the place where Casino manager James Conant introduced ice hockey to the Steel City.

Ice Warms the Hearts of the Investors

In the fall of 1893, the idea was hatched to provide Pittsburgh with a facility that would be a place for theater, recreation and social gathering for “people of stature and the common man.”

The idea sputtered through a committee of capitalists until Conant convinced his boss and head of the Casino, Harry Davis, that the new building could feature an indoor ice skating rink.

The notion of indoor ice skating galvanized the Casino’s construction plan.

After learning that an artificial ice surface was possible, investors were quick to agree to the $400,000 financing, and construction of the Casino was completed before opening to the public May 29, 1895.

The Casino was built at the entrance to Schenley Park in Oakland near the recently completed Phipps Conservancy. Just across the Schenley Bridge, Andrew Carnegie’s “people’s library” would open six months later.

The Casino’s architecture was bold, ornate and magnificent. The exterior was limestone and brick and the roofline was adorned with a thousand wooden corbels and copper cornices. The entry portico featured a large arch and detailed brick work. Above the entry was a grand patio used for parade reviews and political speeches in the summer months.

The first floor had more than 40 palladian windows, 18-feet tall and 6-feet wide, that filled the Casino with ample light. Initially, the heat from the sunlight was problematic for the ice surface but large interior window coverings were added to the eastern side of the building to prevent a greenhouse-effect that softened the ice on the rink.

At night the building glowed with more than 1,500 incandescent lights, 11 arc lights and four white calcium lights highlighting highly-polished oak woodwork. On the main floor, where patrons entered, oak panels stood 13 feet high. The buff and cream stucco ceiling work covered 45,000 square feet and was done by Averall of New York.

Upon entering the building, visitors walked in on a balcony that circled the skating floor 20 feet below. The balcony was 840 feet in length and could accommodate 12,000 people looking down on the skating floor. An article in The Pittsburg Press from December 1885 described a “friendly hockey match” between local hockey clubs in which 10,000 people attended.

A Cool Idea – Just Add Ice

At ice level, which was below ground, the rink was surrounded with three rows of hardwood benches with red velvet cushions. Each end of the rink featured 10 dressing rooms smartly furnished with oil paintings and floor-to-ceiling tapestries. The rooms were owned by politicians and capitalists from the banking, steel, coal and railroad industries and were used for winter carnivals, skating expos and political rallies. In all, the Casino’s management added $140,000 in amenities beyond the original construction cost.

The Casino had a quaint 400-seat theatre that opened into the main floor and could easily convert into a large concert or convention hall. The south end of the building had an elegantly appointed cafe that served theatre patrons.

The Casino also had a ladies’ reception room that was adorned with imported carpeting, lace curtains, stuffed leather recliners and “every other modern day device.” At the side of the ladies’ reception area was the childcare and play area with a matron in charge.

The primary attraction at the Casino, however, was the elliptical-shaped, 225 x 70 foot ice surface. (The standard rink size in the NHL today is 200 x 85). The main floor “bowl” was concrete mixed with a marble chip aggregate and was designed to hold water. The concrete was poured on top of a series of looping “chiller pipes” that carried ammonia gas from the Casino’s ice making room. The ammonia froze the concrete slab and one inch of water on the floor.

“Skating on ice is a pastime that perhaps no one in this city ever before indulged in at this period of year,” claimed an article in a May 1895 edition of the Pittsburg Press. The article also praised the Casino: “The body of ice has remarkable smoothness and the excellence of its surroundings and is unsurpassed anywhere on the globe.”

The Pittsburgh Post was equally full of praise about opening night: “The big ice skating rink was perhaps the best patronized party at The Casino. Hundreds of persons took advantage of the rare opportunity to skate on ice in hot weather, and they had plenty of amusement and excercise.”

Public skating sessions were held only on weekdays. The five cent admission included steel skate frames that strapped over a person’s winter footwear. One thousand pairs of skates were available. Saturdays were reserved for private parties and the Pittsburgh Hockey Club that evolved into the Pittsburgh Keystones – a group of local men from Western University (University of Pittsburgh) and Carnegie Tech.

First Hockey Exhibition

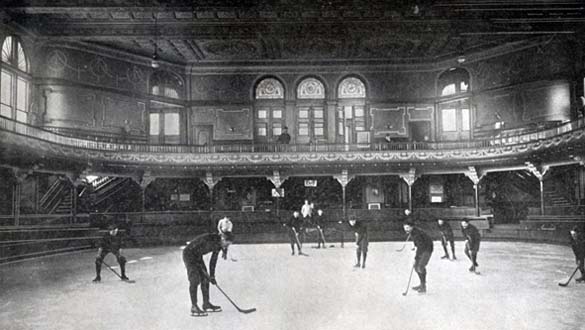

Inside the Casino, the first hockey team in 1895. This is the earliest known image of ice hockey in Pittsburgh

The Pittsburg Press noted a “Great international hockey and polo tournament” opening game at the Casino on December 30, 1895. A team of ten Queens University players met a group of local skaters from Western University and Holy Ghoset and a half hour of exhibition of hockey was played before the polo match.

The following day The Press had this account: “Between 2,500 and 3,000 (despite bad weather) showed how hockey and ice polo should be played when business is meant. Before 9 o’clock the boys lined up and gave an exhibition of hockey. This game has never before been seen in Pittsburgh, and it was a revelation. The Casino players, in truth, didn’t know just what to do with that little flat “puck” used in hockey. They didn’t know whether it was good to eat or whether it was a holiday toy. No account was kept of the hockey score, but the crowd marveled at the work of the visitors.”

The Casino in Ruins

While ammonia was the solution that enabled the Casino to be North America’s first artificial indoor rink, it also was the reason the building was destroyed.

In the early-morning hours of December 17, 1896, an ammonia pipe in the icemaking department began leaking. Firefighters believed the gas mixed with grease and created an explosion. The fire that ensued consumed the equipment room in the rear of the Casino and spread to the ladies’ dressing room. Cold December temperatures caused decreased water pressure for fire hoses, and limited access across the wooden Schenley Bridge gave the fire too much of a head start for the fire brigade.

Less than 40 minutes after the firefighters began attacking the blaze, a larger explosion of the main ammonia storage tank leveled the rear half of the building sending glass and timbers flying across the Schenley Bridge. Newspaper accounts told of flames “shooting hundreds of feet above the park.” The heat was so intense it melted glass at the Phipps Conservancy.

The dense smoke and heavy ammonia fumes forced firefighters to retreat from trying to save the main hall of the building. Adding water to the ammonia only exacerbated the lingering cloud of poisonous gas. The building was totally consumed by fire within an hour. The intense heat, fueled by the heavy oak wood interior, melted the copper cornices along the roof.

Pittsburgh Fire Chief Miles Humphries declared the fire “unmanageable” and forced all firefighters and horse-drawn equipment away from the structure. The Casino flames raged on for an additional six hours and smoldered for two days. The only thing that remained was the large brick smoke stack and a portion of the wall along the bridge side of the Casino. All of the ice skates were gone and a brand-new merry-go-round, valued at $30,000, was destroyed in the blaze.

The Yale hockey team was to have played a series of games against Western University, Duquesne and the Keystones but they were telegraphed and told not to come to Pittsburgh.

The remaining portion of the structure was razed the day after Christmas. The building was “woefully underinsured”- a mere $75,000 was covered.

“It was an oversight. Fire from an explosion of the ammonia tanks was an emergency never contemplated and consequently never provided for,” Casino boss Davis explained to the Commercial Gazette as to why little insurance was carried. “We had taken all other precautions, but neglected the vital one,” Davis said. Investors initially were hopeful that the Casino would rise again, but it never materialized.

Finding a New Home

Local investors, led by political heavyweight Christopher Magee, focused their attention on an old streetcar barn less than a half mile away from the Casino. The devastating loss of the Casino hastened efforts in transforming the Duquesne Traction Company, purchased in 1895, into the city’s new multi-purpose sports and entertainment venue that would become the Duquesne Gardens.

The Gardens opened for public skating on January 23, 1899 and one night later featured a hockey game between the Pittsburgh Athletic Club and Western University of Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh).