FAST FACTS

• Conant was the manager of Pittsburgh’s first two indoor ice rinks.

• Conant convinced dozens of Canadian hockey stars to play in Pittsburgh.

• Conant was credited with bringing the Metropolitan Grand Opera Company to Pittsburgh.

• Conant was one of the first catering managers at Kennywood Park.

• Conant formed the Pittsburgh Hockey League around 1900.

He’s a showman and he knows what entertains people.

CHRISTOPHER MAGEE, one of the original financial backers at the Schenley Park Casino and owner of the Duquesne Garden, on James Conant

JAMES M. KUBUS

Pittsburghhockey.net Editor

He started a love affair that has lasted more than 100 years.

James Wallace Conant was the flamboyant matchmaker who introduced ice hockey to the city of Pittsburgh in 1895 and sparked a romance between a hard-working city and a graceful sport.

With carnival-like enthusiasm, Conant brought the great outdoor Canadian game, inside and to the Steel City when the Schenley Park Casino opened its doors.

In the fall of 1893, an idea was hatched to provide Pittsburgh with a facility that would be a place for theater, recreation and social gathering for “people of stature and the common man.”

In the fall of 1893, an idea was hatched to provide Pittsburgh with a facility that would be a place for theater, recreation and social gathering for “people of stature and the common man.”

The idea sputtered through a committee of capitalists until Conant convinced his boss, head of the Casino Harry Davis, and political heavyweight Christopher Magee, that the new building could feature an indoor ice skating rink.

The notion of indoor ice skating galvanized the Casino’s construction plan; the notion of an indoor skating rink galvanized Pittsburgh’s interest in hockey.

“He is a showman,” said Magee. “He knows what entertains people.”

The showman Conant was born on August 10, 1862 in Portsmouth, Ohio and moved to Pittsburgh with his mother when he was 15.

He took a job as a stewart on a river steamer. “He thought the rivers were interesting and was always amazed by all the activity on them,” a newspaper obituary said of Conant. “He loved looking at the river.”

Conant lived three blocks from the edge of the bluff above the Monongahela River on Gist Street in the Hill District. The busy industry traffic on the rivers was much like Conant’s career; always hustling and bustling with activity and full of potential for commerce.

- Conant’s house at 110 Gist Street in the Hill District has been vacant for two decades and is located a quarter-mile away from the Civic Arena and the CONSOL Energy Center.

He took several jobs in his twenties, working in theater houses in the city’s Hill District, a few downtown night clubs, and worked as a coordinator for a barge company with docks along the Mon Wharf.

At age 36, his involvement with amusements was well known and caught the attention of Davis and Magee. They were convinced Conant would be the man to run the Casino – a building The Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette called “the magnificent palace of pleasure.”

The Casino, operated by the Schenley Park Amusement Company in Oakland, was the envy of the sports and entertainment world. It was considered to be one of the “handsomest amusement buildings in the United States,” according to an Atlantic Architecture report. Luxury boxes, a grand theater, a capacity of 12,000, and an indoor ice skating surface made it an unrivaled complex in North America.

The Casino, operated by the Schenley Park Amusement Company in Oakland, was the envy of the sports and entertainment world. It was considered to be one of the “handsomest amusement buildings in the United States,” according to an Atlantic Architecture report. Luxury boxes, a grand theater, a capacity of 12,000, and an indoor ice skating surface made it an unrivaled complex in North America.

But as much as it was ahead of its time, it also had a short lifespan. The place burned to the ground just 19 months after opening.

In that time, however, the Casino left an impression on modern hockey, thanks to Conant who knew of hockey through a fellow amusement mangager involved with traveling ice skating demonstrations.

Conant convinced his bosses that the city would be entertained by the speed and elegance of hockey. Hockey exhibitions captivated the interest of Casino patrons, and organized games were scheduled on Friday nights after the public ice skating session. Canadian players learned that there was an indoor ice rink in Pittsburgh and that several players were actually paid to play the game in the Steel City.

The artificial ice surface provided the imported players two months of play before they returned home to play in outdoor leagues.

Hockey almost died in Pittsburgh when the Casino burned in just its second season, leaving Pittsburgh without its original multi-purpose facility and Conant without a job.

Conant took his knowledge and moved to New York City to manage the New York Ice Palace where he introduced indoor skating and the game of hockey to Gotham City.

He worked three winters in New York but returned to Pittsburgh for the summers to work at Kennywood Park as a catering manager. He also ran a refreshment stand in Schenley Park on the site of old Casino, perhaps causing him to think about an opportunity lost.

Others were thinking about a replacement for the the Casino. Local investors led by Magee, focused their attention on an old streetcar barn less than a half mile away. The devastating loss of the Casino hastened efforts in transforming the Duquesne Traction Company, purchased in 1895, into the city’s new multi-purpose sports and entertainment venue that would become the Duquesne Garden.

Magee gave Conant a job as a manager and gave hockey a second chance in Pittsburgh.

The Garden opended for public skating on January 23, 1899 and one night later featured a hockey game between the Pittsburgh Athletic Club and Western University of Pittsburgh (University of Pittsburgh).

Conant was ambitious with his expections at the Gardens: Early on, the building was used to host rodeos and circuses. It held a movie theater and an indoor ice skating surface that was unrivaled in North America. The Gardens featured Pittsburgh Golden Gloves boxing and Conant was credited with bringing the Metropolitan Grand Opera Company to Pittsburgh.

The ice surface was nearly 50 feet longer than today’s NHL rinks and had state-of-the-art refrigeration and resurfacing technology. Program covers called the Garden “The Largest and Most Beautiful Skating Palace in the World.” The competition and ice surface garnered the attention of hockey players all across Canada. Many top-notch Canadian players came to play in front of capacity crowds of 5,000 in Pittsburgh.

Conant formed the Pittsburgh Hockey League there, which lead to the first Interscholastic League.

In 1903, Conant left the Gardens to manage the Farmer’s Bank Building, but that job only lasted nine months, after which he worked as a manager of the the Nixon restaurant until September 1905.

Conant grew restless and hoped to move his wife and mother to the Northeast – either Boston or New York – and began exploring business opportunities in those cities.

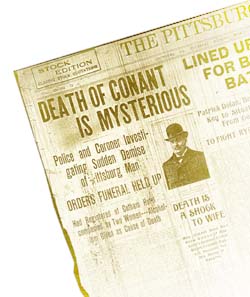

He left for a business trip to Boston and New York in March 3, 1906. Eleven days later, Conant died under mysterious circumstances at the Navarra Hotel in New York on March 14 at the age of 43. Different versions of his death quickly surfaced in Pittsburgh’s afternoon newspapers.

The morning papers said it was sudden and natural. The afternoon papers suggested something much darker: Alcoholism and infidelity, at least. He checked into hotel under the name of J.C. Wallace with two women (“wife” and “friend of wife”). His wife, Margaret, was in Pittsburgh when notified of his death by a Pittsburgh doctor who was said to be traveling with Conant in New York. This doctor signed the death certificate listing cause of death as “heart attack.”

A report in the press said a New York doctor disputed the account of Conant’s doctor: “I am not at all convinced that this man died of natural causes,” the paper reported.

Robbery and murder were also hinted. The Pittsburg Gazette reported the body was moved to the Navarra and that some dispute took place in New York. His personal belongs, including $600 and a diamond stickpin, were missing.

Conant’s body was returned to Pittsburgh and picked up at the Pennsylvanian train station by James Flannery & Brothers Funeral home. Visitation was held at Conant’s home on Gist Street before he was buried at Allegheny Cemetary on St. Patrick’s Day, according to a death notice in the Pittsburgh Press.