Record: 9-27-8

LEADERSHIP

Owner: Benny Leonard

Coach: Odie Cleghorn

Captains: Harold Cotton, Gerry Lowrey

FAST FACTS

• The ownership change was no help to the franchise’s fortunes. The Pirates traded Worters to the New York Americans following a bitter salary dispute before the start of their fourth season, 1928-29. The franchise then went on to win only nine games and went scoreless in 18 games.

• On October 8, 1928 financial problems forced the original owner, Callahan, to sell the team to an ownership group which included Bill Dwyer with fight promoter and ex-lightweight boxing champion, Benny Leonard as his front man.

• The Pirates unveiled gold uniforms trimmed in blue.

• On March 25, 1929 Cleghorn left the team at season’s end and became a referee in the league.

RELATED LINKS

• All-time Pirates roster and scoring

• Pirates goaltending, season by season

• Pittsburgh’s first NHL games

TRANSACTIONS

September 29, 1928 – Mickey MacKay traded to Pittsburgh by the Chicago Blackhawks for cash.

September 30, 1928 – Albert Holway traded to Pittsburgh by Montreal Maroons for cash.

November 1, 1928 – Joe Miller traded to Pittsburgh by New York Americans with $20,000 for Roy Worters.

December 21, 1928 – Frank Fredrickson traded to Pittsburgh by the Boston Bruins for Mickey MacKay and $12,000.

February 12, 1929 – Harold “Baldy” Cotton traded to the Toronto Maple Leafs by Pittsburgh for Gerry Lowrey and $9,500.

February 15, 1929 – Edmond Bouchard was loaned to Pittsburgh by the New York Americans for remainder of 1928-29 season with the trade of Jesse Spring for the loan of Tex White for remainder of 1928-29 season.

I can’t see why Pittsburgh should not be as great a hockey town as New York, or any other city in this country or Canada. This is the home of professional hockey, I am told, and we are going to give the people here just what they deserve – the best we possibly can.

BENNY LEONARD, Pirates new owner, explaining that he would spare no expense to keep the team competitive

An ex-boxer moves in

PAUL CHRISTMAN

Pittsburghhockey.net Contributer

In October 1928, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that famed lightweight boxing champion Benny Leonard, who had retired from the ring in 1925, was the majority stockholder and treasurer in a group that purchased the Pirates from the Townsends. Callahan stayed on as team president. Odie Cleghorn remained in his coaching spot. Cleghorn’s tenure with the Leonards would not be a happy one. Intriguingly, while Leonard stayed in the spotlight, the franchise’s actual new owner remained behind the scenes. He was William V. “Big Bill” Dwyer, the owner of the New York Americans, and a bootlegger.

-

Pirates’ owner Benny Leonard

In July 1927, Dwyer had started to serve a two-year sentence for conspiracy to violate the Eighteenth Amendment (the national prohibition law). The “Bootleg King” was sent to the Atlanta Penitentiary and relinquished controlling interest of the Americans. Dwyer was paroled in August 1928, was back in control of the Americans in September, and was a secret purchaser of the Pirates in October. Syd Howe, forward with the Philadelphia Quakers (formerly the Pirates) said in a 1975 interview with Washington Post writer Robert Fachet that Benny Leonard was actually the team’s general manager. Howe also said that Dwyer’s hand in the Pirates was not a secret to the players. He told Fachet that “the team was owned by Dwyer, who also owned the New York Americans – at least that’s what we were led to understand.” (Decades later, published reports claimed Dwyer became involved, or planned to be involved, in Pirates management before Leonard’s arrival in 1928. No reports from the 1920s could be found to back these claims. These reports have been traced as much as possible and appear to be inaccurate.)

Bert Taggart of the Post-Gazette said that in spite of “the lean gates of the last few years,” Leonard was “satisfied with the prospects this winter.” Leonard claimed he would spare no expense to make the Pirates a first-rate team. He said, “I can’t see why Pittsburgh should not be as great a hockey town as New York, or any other city in this country or Canada. This is the home of professional hockey, I am told, and we are going to give the people here just what they deserve – the best we possibly can.” But it wasn’t exactly in Leonard’s nature to go on a spending spree to improve the Pirates. In 1949, Jim Coleman of the Toronto Globe and Mail interviewed Archie Campbell, the Quakers’ trainer. Campbell remembered a late-night chat with the former boxer in which Leonard said, “With a Jew spending the money and a Scotchman [Callahan] watching where it’s going, they’ll never cheat us, Archie.”

Pittsburgh writers naturally asked Leonard why he, an ex-boxer, would choose hockey as a business venture. In 1930, Leonard told the Philadelphia Inquirer he played goal once (where and when was not revealed), but admitted he didn’t succeed because “I was so accustomed to dodging in the ring that when I went into the nets I dodged every puck shot at me.” At the press conference announcing the sale of the Pirates, Leonard pointed to the success promoter Tex Rickard had in New York with the Rangers. The Post-Gazette also said that after the Pirates got firmly off the ground, Leonard would begin to stage boxing matches at the Duquesne Garden. But it was reported that hockey would preoccupy Leonard at first. At least that was the plan.

It was soon clear that Leonard would have his hands full on the hockey side. The Pittsburgh Press reported that members of a Chicago syndicate had approached Leonard in mid-October with an offer to buy the rights to the Pittsburgh team. Leonard would have realized “a handsome profit” with the deal, the Press said, but he turned it down. He was determined to operate the Pirates himself, in Pittsburgh. Chicago’s interest stemmed from the construction then underway on Chicago Stadium. It was speculated that Chicago could support two NHL teams.

The Press reiterated that the Duquesne Garden’s small size was one roadblock to making the Pirates a success. The paper noted that large enough crowds to ensure a huge profit could not be accommodated at the Garden, and that even so, “people have never warmed up to the professional game as they did to the amateur sport several years ago.” The Pirates’ player salaries were the lowest in the NHL, the Press said, but even with that lower payroll there was still “barely enough money was taken in at the gate to keep the club going.” In late October, Leonard said that the Pirates would have a new arena in 1929. It would seat 15,000 fans, be built in a central location, and be used for other sporting events in the off season. Leonard claimed to have the financial backing to build the arena even if the troubled Town Hall project were to fall through. The Press optimistically noted that the team’s new owners had “unlimited funds” and would “shell out liberally in an effort to make the Pittsburgh club one of the best in the circuit.” Leonard denied reports in the press that said he had the backing of Andrew Mellon, the U.S. treasury secretary.

In his busy first two months in Pittsburgh, Leonard sparred with his team over salaries. He signed five players, but had his troubles with Cotton, Milks, Darragh, and Worters. While Cotton came to terms, the other three players were still unsigned by the October 31 deadline Leonard had set. The NHL then suspended Milks, Darragh, and Wolters from the team at the request of the Pirates. Leonard stood his ground, saying, “I’m no Santa Claus, and they’re not going to make one out of me.” Milks and Darragh soon signed, and their suspensions were lifted. However, the salary dispute with Worters became extremely bitter. The star goalie wanted his annual salary increased from $4,000 to $8,000. Leonard offered $5,200, and later $6,000.

The two sides could not get together. Leonard said Worters would not be sold and that he was confident that he and the goaltender could come to terms. He pointed to what he called a “bad situation” in Pittsburgh, noting that “we do not have the facilities to handle large crowds, and naturally if you do not take in money at the gate you cannot pay it out in salaries.” Leonard said that he had tried to be fair in dealing with his players, offering them all an increase. He contended that the salaries paid to the Pirates compared favorably with those paid by other teams. Worters had a ready reply to Leonard’s claim of insufficient revenue: “That isn’t my fault. I have to work just as hard as the rest of the goalkeepers and be just as good as the rest of them no matter how much they can afford.” Pittsburgh, Worters said, was not where he wanted to stay. He called the city “the only town on the map where I do not get credit for being a goalkeeper.”

The Americans loaned their goaltender, Joe Miller, to Pittsburgh for the season on one provision: Miller had to be returned to the Americans if Worters accepted Pittsburgh’s terms. As the season opened on November 15, Worters was still absent from the ice. Reports that he would ultimately skate in an Americans uniform surfaced. When the Americans’ remaining goalie, Jake Forbes, fell ill, Montreal Maroons goalie Flat Walsh took his place.

On November 20, NHL President Calder seemed to dash the hopes of the Americans when he announced, “Worters will play for Pittsburgh or not at all.” That would only occur, Calder said, when he had lifted Worters’s suspension. Calder believed that if deals for suspended players were allowed, a rich team might create discontent with a player of a poorer one to create a holdout. The rich team could then move in and buy the player. Leonard by then was anxious to get rid of Worters – for the right price. He told the press, “Worters does not want to play in Pittsburgh, and I am going to trade him. The highest bidder gets him, but he is not going to the New York Americans unless I get my terms.” The Toronto Star said that Leonard wanted either center Norm Himes or left wing Johnny Sheppard in addition to Miller, as well as $15,000 in cash. Dwyer’s dual ownership of both the Americans and Pirates could allow one to speculate that he was maneuvering Leonard in order to acquire Worters for the New York team. But from all appearances, Leonard was not subservient to the wishes of Dwyer and the Americans. He took a more independent course than one might expect.

After still more acrimony and league intervention, Worters wound up with Dwyer’s Americans in early December. Leonard had accepted a deal that days earlier he said he would not: for Worters’s services, $20,000 and Joe Miller, who was a competent goalie but not on a par with Worters. The trade reunited Worters with former Pirate Lionel Conacher and solidified the Americans’ defense. Miller, on the other hand, would perform admirably for Leonard under adverse circumstances but in time would wear himself out from the strain. The Pittsburgh Press compared Miller with Worters as the season started. Miller, the paper said, “is cool and dependable under fire and does not lose his nerve at critical stages, something that cannot be said of the suspended star, whose temperament often got the better of him.” On the other hand, Charlie Querrie gave a common impression of Miller in the December 24, 1928 Toronto Daily Star: “Miller in goal is good, but we have seen better.” Miller was no stranger to Pittsburgh. He had played for the Pittsburgh AA in 1916-17 at the start of his career, as well as the Fort Pitt Hornets of the USAHA in 1924-25.

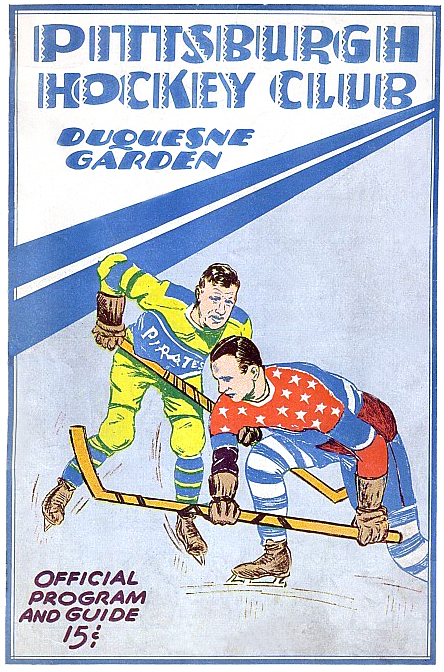

Pirates fans saw more than a change in goaltenders. The Press reported on October 28 that the old Pirate yellow and black uniform colors had been abandoned in favor of “Harding blue” (a light blue that appealed to former first lady Florence Harding) and gold. Newspaper reports confirm that the Pirates did skate in these uniforms. Writers applied “blue and gold” to the Pirates in Press stories through mid-January 1929 (and in one Montreal Gazette story from late November 1928). The cover of a Pirates home program from January 1929 displayed a drawing of a Pirate in a blue-and-gold sweater. Even so, an NHL team directory from 1928-29 and later-day sources claim the Pirates continued to wear black and yellow. Existing black-and-white photos are inconclusive. Team and player shots show what appear to be lighter-shade uniforms, evidently ruling out black. But one publicity photo shows Cleghorn and Leonard in what looks like substantially darker-colored Pirate uniforms with the same design. While two different uniforms might have been used in 1928-29, it’s doubtful that Leonard would have taken on this expense. Also, available news stories for this season did not call the Pirates the “black and yellow” at any point.

Pirates fans saw more than a change in goaltenders. The Press reported on October 28 that the old Pirate yellow and black uniform colors had been abandoned in favor of “Harding blue” (a light blue that appealed to former first lady Florence Harding) and gold. Newspaper reports confirm that the Pirates did skate in these uniforms. Writers applied “blue and gold” to the Pirates in Press stories through mid-January 1929 (and in one Montreal Gazette story from late November 1928). The cover of a Pirates home program from January 1929 displayed a drawing of a Pirate in a blue-and-gold sweater. Even so, an NHL team directory from 1928-29 and later-day sources claim the Pirates continued to wear black and yellow. Existing black-and-white photos are inconclusive. Team and player shots show what appear to be lighter-shade uniforms, evidently ruling out black. But one publicity photo shows Cleghorn and Leonard in what looks like substantially darker-colored Pirate uniforms with the same design. While two different uniforms might have been used in 1928-29, it’s doubtful that Leonard would have taken on this expense. Also, available news stories for this season did not call the Pirates the “black and yellow” at any point.

With the exception of Miller, the Pirate lineup had not changed substantially from the year before. Defenseman Marty Burke, who had come to the Pirates on loan, returned to the Canadiens. Pittsburgh acquired 26-year-old defenseman Albert “Toots” Holway for cash. He had played for the 1925-26 Stanley Cup champion Maroons and most recently for the Stratford Nationals. Holway had suffered a recent ankle tendon injury but was attempting a return to the NHL. He would score four goals for the Pirates in 1928-29. Veteran center Mickey MacKay came to Pittsburgh from Chicago for cash. The 34-year-old MacKay had scored 17 goals in 36 games for the Blackhawks the year before. He had played mostly in Vancouver from 1914 to 1926 before coming to Chicago. MacKay, who would be elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1952, was approaching the end of his career when he played for the Pirates.

Leonard expressed nothing but optimism to the Pittsburgh Press. He said, “I’m really enthusiastic over the chances of our team. I actually think we’ll finish one, two. The team is in condition, which wasn’t the case last year.” The Press reported that the Pirate skaters were as confident of success as Herbert Hoover, who had just been elected president of the United States. Old Duquesne Garden had a new feature – 1,500 additional seats, which would each be sold for 75 cents.

The Pirates played their first game under the Leonard regime on November 15, 1928 at the Duquesne Garden. Leonard used the occasion to make a speech. Although the visiting Boston Bruins took Pittsburgh, 1-0, in overtime, Bert Taggart of the Post-Gazette wrote that the 7,000 fans who jammed the Garden left “satisfied that they had received their money’s worth as well as convinced that the new owners of the Bucs have a formidable entry in the field this year.”

The Pirates followed up with a 3-1 loss at Detroit, but they earned their first victory in their third game with a 2-0 win over the lowly Blackhawks in Chicago. The satisfaction of Pittsburgh’s hockey fans was then severely put to the test. Many must have wondered whether all of the season’s excitement was spent in the endless Leonard-Worters salary dispute. The Pirates’ next win following the November 20 Chicago victory would come on December 20 in a 1-0 home win over the Americans.

Miller did his job in goal in the Pirates’ first 16 games, which completed the 1928 end of the schedule. The Pirates surrendered 22 goals in that span. Even with league-wide goal scoring significantly reduced owing to the NHL’s stiffened offsides rules, the goals-against figure compared favorably with that of other teams (though by all accounts the Pirate defense did not lend Miller adequate support). But over those 16 games the Pirates scored a league-low 13 goals and were shut out 10 times. On December 9, Cleghorn dispatched a telegram to managers of other NHL teams (except 1-7-1 Chicago, whose only win had come at the Pirates’ expense). Minor-league squads got the message too. Cleghorn’s offer was direct: “I’ll trade any man on the club, providing of course, that I get an even break in the deal.” The managers were asked what they had to offer. At the time, the Pirates had a 1-6-3 record (the lone win coming against Chicago). The Press said that only Miller, Drury, and Holway were performing well, but the others were playing “far below their true stride.” The Pirate bosses reportedly thought the players, particularly the forwards, tended to be selfish and absolutely refused to work together. Leonard gave Cleghorn full authority to acquire players by trade or, if that did not work, by purchase. The pocketbook was said to be open.

Ex-Yellow Jackets coach Dick Carroll was by this time coaching in Tulsa in the AHA. He had said on a recent visit to Pittsburgh that he would take any player the Pirates would offer. But he was offered three Pirates and turned down each of them. The Pirates made their first trade came on December 21. Mickey MacKay had only scored one goal in 10 games for Pittsburgh. Max Hannum of the Pittsburgh Press wrote that he might have been out of condition or unable to adjust to the “individualistic tactics” of his teammates (he made passes to where other Pirates were not). The Pirates dispatched MacKay and $12,000 to the Boston Bruins for 33-year-old center Frank Fredrickson.

Fredrickson had played with Detroit and Boston in the NHL since 1926 and with Winnipeg and Victoria before that in a career extending back to 1913. He would be elected to the Hall of Fame in 1958. The lifetime statistics of Hall members MacKay and Fredrickson, both now in the latter portions of their playing careers, were similar. Fredrickson had three goals and one assist in 12 games with Boston in 1928-29. As Fredrickson told Stan Fischler in the book Those Were the Days (Dodd, Mead & Company, 1976), he and Bruins manager Art Ross had had a rift, and he was being used less and less. By now, Fredrickson was pretty much relegated to penalty killing. Nevertheless, he was “heartbroken” over his trade to Pittsburgh. Fredrickson liked Boston and was settled there. He also felt bad for MacKay, who was upset over the terms of the trade.

Fredrickson wasn’t enough to turn around a bad situation in Pittsburgh. The new year of 1929 brought little cheer to Duquesne Garden crowds. The Pirates were winners in only three out of eleven games in January. Back-to-back shutout victories on January 19 versus Detroit and January 20 versus the Americans marked the final time the Pirates-Quakers franchise would win two consecutive games. The January 20 win over the Americans, played at New York, would be the second-to-last road win for the Pirates-Quakers. (The final road victory would come over two years later, after the Pirates’ move to Philadelphia.) The Pirates went on a 2-15-2 crawl after January 20, quite the opposite of the late-season surges of their playoff years. The team was not helped in late January and early February when Odie Cleghorn suddenly took ill. Leonard and his brother Charles, the team’s secretary, temporarily took over the coaching duties. Attendance fell off when the team’s playoff hopes disappeared. The Post-Gazette noted that only a “handful” of fans appeared for the last half dozen Pirate home games.

-

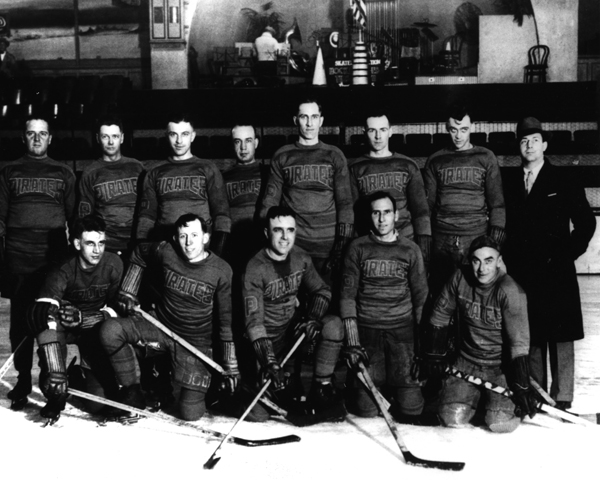

1928-29 Pittsburgh Pirates: Front Row “Toots” Holway, Duke McCurry, John McKinnon, Harold Cotton and Herb Drury. Back row: Odie Cleghorn, Mickey Mackay, Hibbie Milks, Joe Miller, Roger Smith, Art Lowndes, Tex White and Benny Leonard.

In a mid-February trade of left wings, long-time Pirate Harold Cotton went to Toronto for Gerry Lowrey and $9500. Lowrey, who became the third Pirates captain, was a decent scorer. But the swap ultimately benefited the Maple Leafs. In his memoir, If You Can’t Beat “em in the Alley (McClelland and Stewart, 1981), Leafs owner Conn Smythe said he had taken a bit of an advantage of Benny Leonard in the exchange.

The “lean gates” in Pittsburgh resulted in a relocation of the Pirates’ last two home games versus the Bruins and Rangers to Boston and New York. Leonard outwardly took the site switches in stride. He said, “We realize the situation and don’t blame the fans for not patronizing a team not in the running and playing losing hockey.” The Pirates lost the relocated games by scores of 3-1 to Boston and 4-3 to the Rangers. Relocation also hit Chicago. Ten Blackhawk home games were played at road sites in early 1929. It wasn’t a matter of lean gates. The last-place Hawks were caught between a lease that expired at the old Chicago Coliseum in January and a delay in opening the new Chicago Stadium. Chicago played its home games in February and March 1929 in Detroit, as well as Fort Erie and Windsor, Ontario. On January 20, at the last home game actually played in Chicago for the season, 7,000 fans of the 4-16-3 Hawks jammed the tiny Coliseum and another 3,000 had to be turned away.

Pittsburgh finished the season at 9-27-8, mired in fourth place, and 21 points out of a playoff spot. Chicago was the only NHL team with a poorer record. Even Miller’s usually reliable goaltending had withered over the long haul. The Pirates had an NHL second-worst goals-against total of 80 goals in 44 games played during a season where goals were hard to come by, thanks to the league’s stringent offsides rules. Boston’s league-leading offense had put the puck in the opposition net only 89 times in their 44-game schedule. The NHL set itself to consider ways to increase scoring.

It came as no surprise that the Pirates were once more NHL doormats in attendance for 1928-29. On the positive side, Pittsburgh’s total rose to 59,790 from the previous year’s 40,000. Benny Leonard had provided some incentive for Pirate fans to come out at first. However, thanks to the Pirates’ poor second-half showing, crowd levels had dropped precipitously as the season wore on. Pittsburgh’s total was still well behind that of Chicago, the team with the second-lowest attendance figure. The cellar-dwelling Blackhawks had still drawn 75,506 even though they had won only seven games and skated at the puny 8,500-seat Coliseum when they weren’t playing “home” games out of town. The Boston Bruins led all teams with 294,518, thanks in large part to their new 14,000-seat Boston Garden. The Bruins enjoyed a total that was almost five times that of the Pirates.

The last word on the Pirates’ future prospects went to Leonard: “Next season we hope to have a championship team and be able to hold the interest of the fans from the first to last game. There will be a new team here next winter, one we believe will win a money position.” That induced Bert Taggart of the Post-Gazette to comment, “Leonard’s declaration that the team would be back here next season sets at rest the many rumors current that the Pirates franchise would be transferred to another city.” Or would it?

Cleghorn clears out

It wouldn’t have been an off-season without more rumors on a possible franchise move for the Pirates. In mid-March, Bert Perry wrote in the Toronto Globe, “Newark has built, or is building, a big arena, and the Pirates may be transferred there.” But on March 26, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette said construction had been abandoned. Philadelphia was still rumored to be in the running. Leonard reportedly favored Newark over Philadelphia because the Quaker City was not supporting its Philadelphia Arrows of the Canadian-American Hockey League. But Newark had its problems too. The Newark Bulldogs of the CAHL had played in 1928-29 but dropped out of the league at season’s end. The New Jersey city was also next door to New York, home to the Americans and Rangers.

In the end, Leonard stayed with Pittsburgh. But he had to search for a new coach and deal with some dirty laundry. Odie Cleghorn resigned as Pirates coach March 25. The Post-Gazette said that Cleghorn was not getting along with Pirate management and that a lack of discipline that had characterized the “unruly” Pirates lay behind the resignation. Cleghorn pointed to another point of friction as he quit. He said that the trades involving Worters, Conacher, Cotton, Arbour, and White had been made against his wishes. When the Pirates traded Cotton to Toronto and loaned White to the Americans, Cleghorn said, management had even made the deals without his knowledge. The Post-Gazette said Cleghorn had become merely a “nominal” leader. Cleghorn said in parting that there were “too many bosses on the club to suit me and I didn’t like the way they ran things.”

Club secretary Charles Leonard said the Worters deal was made before Cleghorn had signed his contract and that the other transactions had helped the Pirates. He also said that it was “amusing” that early in the season, Cleghorn had denounced his players and sent telegrams to owners of other teams that said that all of the Pirates were on the market. Leonard did not specifically comment on the infamous Conacher-for-Langlois deal with the New York Americans, which had occurred under the ownership of the Townsends.

Columnist Regis M. Welsh of the Post-Gazette came down on the side of management. He wrote that the morale of the Pirates had weakened when it became clear that Cleghorn didn’t force some players to be temperate “on invasions of the Canadian oasis.” (Prohibition was at this time the frequently circumvented rule of law in the United States, leaving Canada as a refuge for imbibers.) Welsh acknowledged that Cleghorn had taken the Pirates to the playoffs twice. But he pointed out, “Once they might have won had they not been drinking champagne out of a ginger ale bottle.” Welsh said that while Cleghorn was an “intimate friend” to the Townsends, the Leonards regarded Cleghorn as an employee and expected him to produce results. Leaving their relationship with Cleghorn particularly strained, the Leonard regime would now hand the coaching reins over to another experienced hockey man in the hope that their franchise’s downhill slide could be reversed.

<<< 1927-28 Pittsburgh Pirates … 1929-30 Pittsburgh Pirates >>>

1928-29 Pittsburgh Pirates

| Skater Stats | Regular Season | Playoffs | ||||||||||

| # | NAME | POS | GP | G | A | P | PIM | GP | G | A | P | PIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Harold Darragh | LW | 43 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | Hib Milks | LW | 44 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 22 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | Frank Fredrickson | C | 31 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 28 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8 | Herb Drury | C | 43 | 5 | 4 | 9 | 49 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10 | Tex White | RW | 32 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 18 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 3 | Rodger Smith | D | 44 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 49 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | Harold Cotton “C” | LW | 32 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 38 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | Albert Holway | D | 40 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 20 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 9 | Gerry Lowrey | LW | 12 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 5 | Frank McCurry | LW | 35 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 12 | Bert McCaffrey | RW | 42 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 34 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 11 | John McKinnon | D | 39 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 44 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 7 | Mickey MacKay | C | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 10 | Edmond Bouchard | LW | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 14 | Jesse Spring | D | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Goalie Stats | |||||||||||||||

| # | NAME | GP | W | L | T | OTL | SOL | Min | GA | SO | GAA | G | A | P | PIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Joe Miller | 44 | 9 | 27 | 8 | — | 2780 | 80 | 11 | 2.00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |