FAST FACTS

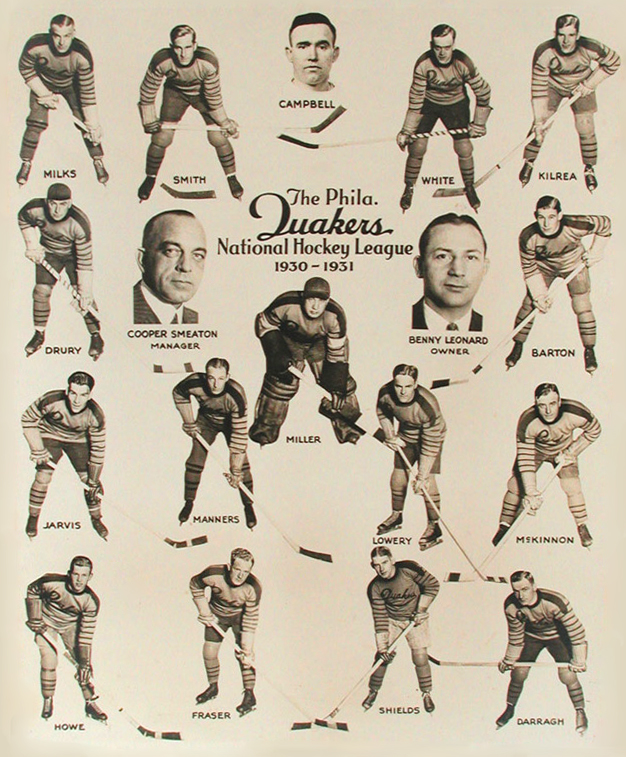

• On October 18, 1930, 13 players were transferred to the Philadelphia Quakers after Pittsburgh franchise relocated:

Cliff Barton, Harold Darragh, Herb Drury, Gord Fraser, Frank Fredrickson*, Jim Jarvis, Gerry Lowrey, Ren Manners, John McKinnon, Hib Milks, Joe Miller, Rodger Smith & Tex White

* Fredrickson was released by Philadelphia two days later.

• The Quakers select Cooper Smeaton, the NHL’s referee-in-chief, to replace Frank Fredrickson as coach of the team.

• Philadelphia fans subject the Quaker players to “caustic comments” in their first game and head for the exits during the first period.

• The Quakers share the Philadelphia Arena with the Philadelphia Arrows of the Canadian-American Hockey League. Arrows crowds average 4,000, while the Quakers average only 2,500.

• On Christmas night, the Quakers and Bruins treat fans to two colossal fights that policemen had to break up during an 8-0 Philadelphia defeat at the Boston Garden.

• Benny Leonard must fend off reporters’ questions about moving the Quakers to another city only two months into the season.

• The Quakers lose 15 straight games, an NHL record that stood until 1974-75.

• The final record of the Quakers (4-36-4) produced the lowest winning percentage of any NHL team except (by a very small margin) the 1974-75 Washington Capitals.

• One Quaker, Syd Howe, would be enshrined in the Hockey Hall of Fame for his later stellar play for the Detroit Red Wings.

RELATED LINKS

• All-time Pirates roster and scoring

• Pirates goaltending, season by season

We are rebuilding our team, and it is going to take a little time.

FRANK FREDRICKSON, new coach of the Pirates, calling for patience in the team’s last ditch effort to improve

Pirates move east; become Philadelphia’s first NHL Team

PAUL CHRISTMAN

Pittsburghhockey.net

The Philadelphia press played the Quakers up as the city’s newest team with the expected improvement over 1929-30 under the franchise’s third coach, retired NHL referee in chief Cooper Smeaton. Smeaton was making his first and only try at managing an NHL team. Leonard told the Philadelphia papers that his players would benefit from Smeaton’s stricter approach to coaching. “What my team needed last year was a boss,” Leonard remarked. He said that some of the Canadian-born players had never heard of Prohibition. Leonard’s line, then, was that team discipline was still an issue (and the primary one) in the final year in Pittsburgh. The Quakers had released Fredrickson. He, like Odie Cleghorn, was in Leonard’s eyes too lenient with the players. Perhaps Smeaton, as a former referee, would keep the players in line. Leonard said, “Smeaton will rule with an iron fist and if necessary we may have a few policemen around to keep order.” Leonard did not publicly own up to another problem: his team had too few quality players. Smeaton had little to work with.

Syd Howe said this about about Smeaton to the Washington Post in 1975: “He was good, but he didn’t have the material.” Archie Campbell, the Quakers’ trainer, once told sportswriter Bill Roche that Smeaton “didn’t have a chance, but he certainly knew his hockey.” For his part, Fredrickson considered suing the Quakers to get a financial settlement of the remaining two years on his contract. He ultimately decided not to pursue his case. As it had been with Odie Cleghorn, the reign of another Pirates coach concluded with much bitterness between Leonard and the man behind the bench.

On loan from Ottawa, Leonard acquired forwards Syd Howe and Wally Kilrea, as well as defenseman Allen Shields. The three would become fine players in time, but in 1930 they lacked NHL experience. Leonard said, “This is only the first move to bring a winner here. We must make a good start and I will spare no expense to give the fans what they want.” Whether Leonard had the money to back his promises was questionable. In one tale about the Pirates or Quakers (depending on the source), the team’s coach was forced to fund road trips out of his own pocket. The coach and team were nearly stranded at a train station when a check intended to cover the team’s trip to Chicago bounced. Leonard could not be reached, but a phone call to Leonard’s lawyer produced the needed money just as the Chicago-bound train was about to pull out. Syd Howe told the Washington Post, “Those were depression years and we were making pretty good money, $3,500 to $4,000. We were getting paid pretty regular, too, although sometimes it was an off-and-on thing.”

Hockey writers outside of Philadelphia predicted that the Quakers would do no better than the Pirates. Leonard Cohen of the New York Post wrote shortly after the season opened, “The Philly hosts look like the weakest force in the circuit on paper; they’re every bit of that on the ice.” The more upbeat Philadelphia Inquirer played the upcoming opening game with the New York Rangers as another chapter in the sports rivalry between New York and Philadelphia, then best shown by baseball’s New York Yankees and Philadelphia Athletics – American League pennant and World Series winners from 1927 through 1930.

Leonard was as much the promoter in Philadelphia that he was in Pittsburgh. He proclaimed, “I feel certain Philadelphia hockey fans will like the men who will represent this city in the National League. I want to produce a winning club. If I don’t, it won’t be my fault.” Coach Smeaton, Leonard said, knew the game “from A to Z.” That had to be why Smeaton showed more caution. He told the Philadelphia writers, “I know there are better teams than the Quakers in the league, but we are going to have a fighting combination.” The Quakers were not ones to avoid a fight. But they would soon show that the previous year’s Pirates and their 5-36-3 record had not quite hit rock bottom.

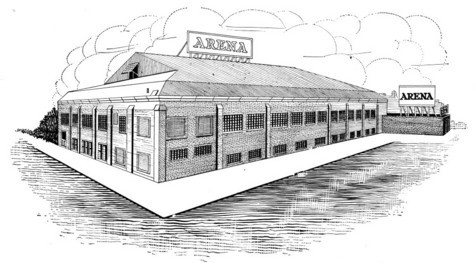

The Philadelphia Arena, the home ice of Leonard’s Quakers as it had been for the Arrows since 1927, was 25 years younger than the aged Duquesne Garden. Still, the 10-year-old Arena was a small rink with poor sightlines. It was already quite a few steps behind the larger and newer rinks of the NHL. On October 20, an unnamed Philadelphia Inquirer columnist writing under the name of “The Old Sport” put in his two cents under the heading “Can Philadelphia Accommodate the Quakers?” A self-proclaimed hockey enthusiast, the Sport said he was thrilled that Philadelphia would now have the Quakers as well as the Arrows. But in his moments of calm he had his doubts. He wrote, “Philadelphia is not ready for National League hockey – not because the fans would not support it, but because we have not a suitable arena in which to stage the games and accommodate the crowds that would want to see it.”

The Philadelphia Arena, the home ice of Leonard’s Quakers as it had been for the Arrows since 1927, was 25 years younger than the aged Duquesne Garden. Still, the 10-year-old Arena was a small rink with poor sightlines. It was already quite a few steps behind the larger and newer rinks of the NHL. On October 20, an unnamed Philadelphia Inquirer columnist writing under the name of “The Old Sport” put in his two cents under the heading “Can Philadelphia Accommodate the Quakers?” A self-proclaimed hockey enthusiast, the Sport said he was thrilled that Philadelphia would now have the Quakers as well as the Arrows. But in his moments of calm he had his doubts. He wrote, “Philadelphia is not ready for National League hockey – not because the fans would not support it, but because we have not a suitable arena in which to stage the games and accommodate the crowds that would want to see it.”

The Sport was half right. The Arena was unsuitable for an NHL team. But many Philadelphians in 1930 did not yet share the columnist’s enthusiasm for hockey and weren’t ready to support the Quakers. Leonard had recognized this a year earlier. He then was said to prefer moving the Pirates to Newark rather than Philadelphia because of the lukewarm support the Arrows had received in their first two seasons. Interest in the Arrows had increased in 1929-30, when the team improved on its sixth-place finishes of years 1 and 2 and rose to second place and a playoff spot. But the first Arrows home playoff game against the Boston Tigers only attracted an unremarkable CAHL crowd of 3,500. About one-third of the Arena seats were empty. Syd Howe was on target when he recalled his Quaker days for the Washington Post in 1975: “People in Philadelphia were not educated to hockey at that time.”

The 1920 opening of the Arena (originally named the Philadelphia Ice Palace) gave Philadelphia-area residents their first chance to skate regularly since the West Park Ice Palace at 52nd and Jefferson Streets had burned down in March 1901. College and amateur hockey teams were the first to play at the new rink. The CAHA Arrows came along in 1927, and the Quakers marched into town just three years later. The Arrows and particularly the Quakers played before sparse crowds. Even after the Quakers departed, the support Philadelphia fans would give their many minor league teams through the early 1960s would be uneven. The low point had to be when the 1951-52 Philadelphia Falcons of the Eastern Amateur Hockey League never made it out of 1951. The team disbanded in December because of poor attendance. Meanwhile, the Pittsburgh Hornets received consistent fan support from 1936 to 1956 and from 1961 to 1967. (The break from 1956 to 1961 occurred when the Duquesne Garden was at last demolished and the Civic Arena was erected.)

For all their troubles in Pittsburgh, Benny Leonard’s Pirates had deserted prime western Pennsylvania hockey country (even if temporarily) for Philadelphia, a city less likely to embrace the sport with brotherly love. Leonard’s downtrodden team would face tough sledding when it tried to appeal to Philadelphians. These were fans who were only starting to grasp hockey but through experience could spot a bad team right away. And clearly, the less success the Quakers would have in Philadelphia, the rockier the NHL club’s road back to Pittsburgh would become. Or the less chance it would have to survive altogether.

Leonard dressed his ushers in tuxedos for the first Quakers match, played in Philadelphia on November 11, 1930. Colorful flags hung from the ceiling tried to enliven the drab Arena. The Quakers skated out in new uniforms preserved the orange and black of the 1929-30 Pirates. But the visiting Rangers won 3-0. The crowd of about 4,000 started to make sarcastic remarks, and many left the Arena during the third period. Only 2,000 bothered to appear for the second Quakers home game a week later.

Bert Perry of the Toronto Globe wrote after the Quakers’ second game (a 4-0 loss at Toronto) that Smeaton evidently did not favor “the defensive style of play which characterized the former Pirates.” But if Smeaton wanted to make the Quakers more offense-minded, he lacked the firepower. Charlie Querrie of the Toronto Star said, “The Quakers have a whole raft of forwards but outside of Milks and Darragh they are not up to much.” Querrie also considered the Quaker defense weak, offering Joe Miller little protection in goal. He concluded that if Smeaton could “make a high class hockey club out of that Philadelphia outfit he deserves all the medals.” Darragh would soon be traded away. A worn-out Miller would soon turn the netminder’s job over to Wilf Cude. Milks would be left to hold down the fort with promising but inexperienced youngsters like Cude, Syd Howe, Wally Kilrea, and Allen Shields.

After starting out at 0-4-1, the Quakers upset Toronto on the Maple Leafs’ first visit to Philadelphia, 2-1. The win stunned the Leafs, who had opened their season with five straight shutouts. Some dared to hope. Earl Eby of the Philadelphia Bulletin noted that fans leaving the Arena were “dizzy from the excitement.” Smeaton told the Philadelphia Record, “It took us some time to get started but I think we are now in proper condition and we can defeat many of the teams in either the Canadian or American divisions.” Bert Perry of the Toronto Globe later revealed that the Leafs had taken it easy for two periods in this match. Their comeback try in the third failed thanks to Joe Miller’s valiant goaltending in the Quaker nets.

Quaker opponents went out of their way not to make Toronto’s mistake, and succeeded. The Philadelphians followed up their victory with 15 consecutive defeats, at that time an NHL record. After the sixth loss in a row, Leonard said he’d eat only one meal per day until the Quakers won. The Philadelphia Inquirer‘s Stan Baumgartner remarked that the former boxer might qualify for the flyweight division before the end of the season. But perhaps because the Quakers had lost three games in a row by a single goal at that point, Baumgartner was still not abandoning hope. He wrote, “Someday they will click – find that missing link and then the victories will pour in.” Leonard only got thinner, and the Quakers’ missing link remained among the missing.

The most memorable Quakers loss had to be the 8-0 massacre versus the Bruins at the Boston Garden on Christmas night 1930. Two massive fights that drew in almost every player except the goalies broke out in the third period. A dozen policemen, all slipping and sliding on the ice, were called on to restore order in the first outbreak. Both clubs were soon fined. The Quakers, winners of only one game so far, asked the NHL to use the playoff money they would supposedly earn in the spring to pay their fines.

Leonard and Smeaton blended in younger players during the season. Former Pirates and Yellow Jackets were traded or let go. Out of five original Pirates who started the season with the Quakers, only Hib Milks made it to the end of 1930-31. In December, after Darragh was traded to Boston for wingers Ron “Peaches” Lyons and Bill Hutton (who would spend only two months with Philadelphia), Smeaton told the press, “I’m going to build the Quakers for next season, and I’m going to do it with youngsters.” But Smeaton’s “fresh young talent” could provide only so much immediate help, and the losses still continued to mount. The CAHL Arrows drew more fans than the NHL Quakers. An Arrows crowd would average 4,000 fans, versus 2,500 for Leonard’s squad. In January 1931, Leonard denied press reports that he might transfer the Quakers to another city.

Leonard was having just as rough a season in the books as on the ice. In spite of the Philadelphia Arena’s deficiencies, Leonard paid substantially more rent for its use than he did for the Duquesne Garden. In February 1931, Ralph Davis of the Pittsburgh Press reported that Leonard way paying $38,000 per year rent for the Arena, versus $12,000 per year for the Garden. Davis said Leonard was taking in an average of $2,000 per night at the Arena. The Quakers played just 22 home games (for a take of $44,000 for the season, assuming Davis’s figures to be accurate). Not much would have been left over after the rent had been paid. Leonard said at the time that he had lost $50,000 in Pittsburgh in 1929-30, and that he would lose $80,000 in Philadelphia in 1930-31.

The team wasn’t missed back in Pittsburgh. “Benny Leonard’s Pirates in the Quaker City are starving,” Ralph Davis of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette bluntly noted in mid-January. It was a rare post-move acknowledgment of the former Pittsburgh franchise in the city’s press beyond very short reports on out-of-town Quakers action. In Pittsburgh, the torch had been passed to the International League Yellow Jackets.

The Quakers ended 1930-31 with a final 4-36-4 record for a .136 winning percentage, the second-worst pace in NHL history. Only the 1974-75 Washington Capitals, who won at a .131 clip, have fared worse.

On September 26, 1931, the NHL suspended the Ottawa Senators and Philadelphia Quakers franchises for one year. Canadian papers mourned the loss of the once-proud Senators franchise but said the Quakers would not be missed. Even the Philadelphia press briefly noted the Quakers’ banishment and forgot the team from that moment on.